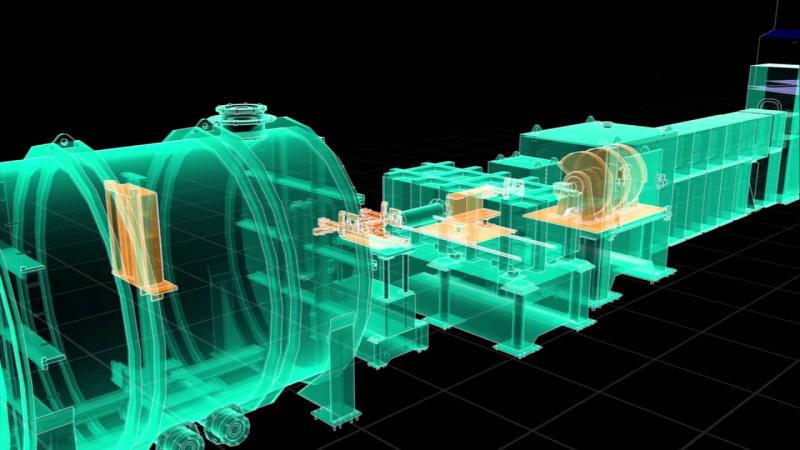

Platypus - Neutron Reflectometer

Reflectometry, along with strain scanning, has been the major growth area in neutron scattering since its inception 20 years ago.

While the first neutron reflection experiments were originally performed in the early 1950s (to determine the fundamental properties of the neutron interaction with the elements), it was first used as a quantitative tool for materials science by Gian Felcher in Chicago (to study magnetic flux penetration in superconductors) and the Oxford group (to study soft matter on surfaces) in the 1980s.

Since then the method has taken off for the study of all-manner of surface-science and interface problems, particularly related to the multi-$B magnetic recording industry and for polymer coatings, biosensors and artificial biological membranes.

For instance, at the NIST reactor (Washington DC), there are now three neutron reflectometers, the latest being fully funded by the National Institutes of Health for the study of biological molecules in membranes.

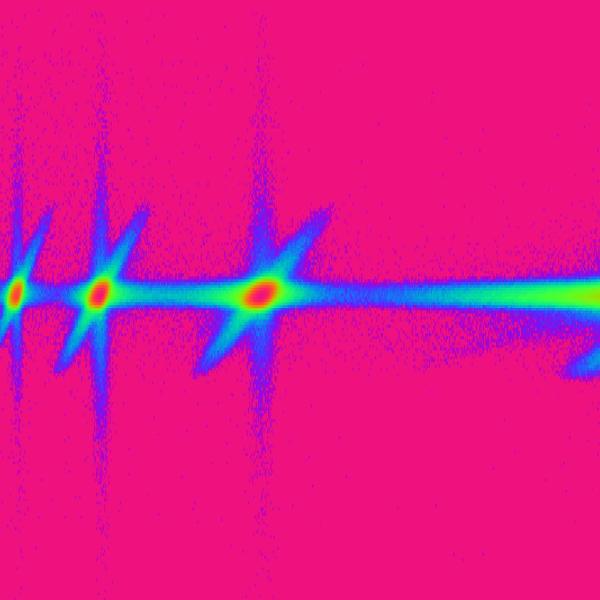

Reflectometry is similar to small-angle scattering in the sense that it is sensitive to lengths on the nanoscale (between 1nm and 100nm), but it is done in reflection rather than transmission geometry. It contains interference information like that routinely seen, by eye, as the coloured sheen from oil films on water.

Reflectometry is typically performed in a line geometry, rather than with pinholes. To get a good result, very perfect surfaces must be used, typically with depositions on commercial silicon wafers or other polished substrates (e.g. salt, quartz, glass, MgF2, etc.).

Free surfaces (e.g. a water or oil surface) can also be used, and special cells available to study solid-liquid interfaces (we have one). Experiments can be done under electrolytic action or shear. There is sometimes scattering away from the perfectly reflected specular beam, called diffuse scattering, and this contains quantitative information about the roughness of the surface(s) and about in-surface structure.

Reflectometry can be performed with both neutrons and X-rays, and we have purchased a state-of-the art X-ray reflectometer to complement our neutron reflectometer. Neutrons give different contrast, but are particularly suited for soft-matter systems in which H-D contrast variation is used, and magnetic materials using polarised neutrons and polarisation analysis.

Some of the most exciting scientific problems tackled with neutron reflectivity include:

- in soft matter, self-assembly of silicate structures at air-water surfaces, the nature and properties of lung surfactants, proteins in membranes, how polymers behave when confined, and so on.

- and in magnetic materials, determining the magnetisation of an iron monolayer, determining the magnetisation of a grain boundary in nickel, studies of interface roughness and magnetic direction across the interfaces in computer hard-drive read-heads.

Our scientific highlights include plasma-polymer coatings for biopassivation (with CSIRO), titania nanoclusters embedded in polymer matrices (with ANSTO-IMES), a commercial Ni-Ti multilayer system, and polymer layers deposited on Si (with the Ian Wark Institute).

The instrument is named after the Australian mammal platypus Ornithorhynchus anatinus.