Published on the 26th May 2020 by ANSTO Staff

Key Points

-

Linking traditional indigenous environmental knowledge and modern scientific data brings benefits

-

Indigenous weather cycles, based on observations in nature, are more appropriate than the traditional four seasons for interpreting pollution data

-

ANSTO is a specialist centre for radon measurements and the supply of radon detectors

Please note that this content includes a reference to a deceased Aboriginal person.

Scientists who study the atmosphere often use seasonal averages in their studies of pollution, because seasonal variability acts as a driver of changes in pollution.

Dr Scott Chambers, a member of ANSTO’s expert radon team, was well aware that weather in many regions of Australia did not conform to the traditional four European seasons that we are all familiar with.

However, he was unaware that an alternative seasonal model existed until he learned about work being undertaken by a group at the University of Wollongong (UoW) who were using Indigenous knowledge of weather cycles to better understand seasonal variability in Sydney’s air quality.

The Centre for Atmospheric Chemistry group, led by Prof Clare Murphy, had combined information from members of the Dharawal and Darug communities with climatological records to determine a meaningful set of natural weather cycles for the Sydney region that had a consistent seasonality of their own. Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub Indigenous research intern Stephanie Beaupark was the lead author of the study.

ANSTO’s former Dharawal cultural advisor, the late Les Bursill, was among the Indigenous representatives who contributed to the project.

“We hoped this more locally-applicable information would help us understand controls on pollution variability around Sydney—better than the adopted European seasons do,” said Chambers.

“Although interviews with traditional knowledge holders were unable to arrive at a conclusive answer as to an exact number of Indigenous seasons, what they did provide was useful descriptions of Sydney weather conditions for specific periods, such as hot/wet, cold/still or cool/dry,” said Chambers.

In order to resolve inconsistencies in the timing of when these conditions changed, Prof Murphy’s group used a mathematical clustering technique and high-resolution weather data to arrive at a model with six seasons.

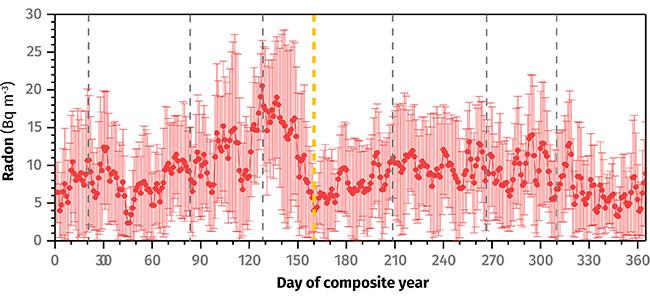

Changing nocturnal radon concentrations across the year. Vertical lines represent a six-season cycle from indigenous descriptions. The yellow dotted line indicated where a seventh seasonal cycle falls consistent with radon data. First and last segments are part of the same cycle.

“Interestingly, when I looked just at the radon data, a seven-season cycle seemed to emerge. The main difference compared with the six-season mathematical model occurring just before mid-year,” said Chambers.

Independently of the mathematical analysis, an inspection of Sydney temperature, wind speed and rainfall data, firmly guided by the Indigenous seasonal descriptors of the Dharawal and Darug communities, also strongly indicated a cycle of seven seasons with transitions in good agreement with the radon observations (see chart above).

“If we use the four European seasons to interpret Sydney’s pollution data, the time of peak pollution occurs illogically at a split between two seasons. Whereas, if we adopt the Indigenous seasonal cycles, the time of Sydney’s peak pollution falls entirely within a single season when local average synoptic weather patterns result in very low levels of atmospheric mixing,” said Chambers.

The ‘cold/still’ season usually occurs between May and early June, when high-pressure systems sit over Sydney. High-pressure systems are associated with dry air sinking down, no clouds, little wind and very stable nights.

“This is a time of the least mixing in the atmosphere at night and pollution builds up the most,” explained Chambers.

“And because it is cold, people use heating. About 10% of people in Australia still use wood fires that result in high emission levels. The combination of high emissions and poor mixing can at times produce high pollution levels. Our measurements of radon levels peak in this period.”

When the winds kick in later in June, the radon levels drop.

“The Indigenous seasonal groupings tend to explain the behaviour of pollution, mainly changes in mixing events, much more clearly than the European seasons,” said Chambers.

Related research on Indigenous seasonal knowledge

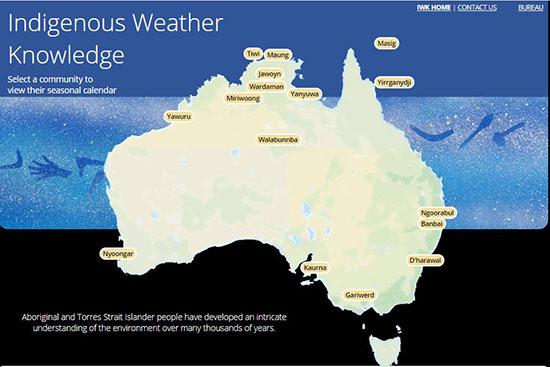

Credit: ABC News, 'Indigenous seasons across northern Australia', ABC Education

Academic researchers, who work in this area, including a group from the CSIRO, have found that indigenous seasonal knowledge, involving the weather and seasonal cycles of plants and animals, is linked to cultural activities and land use.

James Cook University researchers found that seasonal knowledge emphasises cyclical processes that are embedded strongly in place and the ecology of that place.

Basic knowledge of the environment has links to astronomy, weather, landscape, as well as plants and animals, to maintain the abundance and diversity of food and other resources.

The CSIRO and UoW researchers noted that seasonal weather conditions were described as hot, cold, wet or other descriptors.

Indigenous people also described more detailed weather conditions, such as frost, wind direction, cloud patterns and they were sometimes related to events in the landscape.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology shares Indigenous weather knowledge (see map above) for numerous locations around Australia on their website. Dharawal seasonal descriptions are provided for the Sydney area.

The BOM stresses that indigenous information consists of an intimate knowledge of plant and animal cycles and contains details of the intricate connections in the natural world.

Observations of the plant and animal kingdoms have been collected over millennia.

They reflect the deep Aboriginal philosophy that 'all things are connected', and that subtle natural linkages are present, which can reveal much about climate and weather.