Published on the 14th August 2020 by ANSTO Staff

Key Points

-

Once in the ocean and exposed to UV sunlight and oxygen, microstructural changes take place that enhance the breakdown of microplastics and their entry into the natural carbon cycle as carbon dioxide

-

When the polymer chains are cut, the structure changes significantly

-

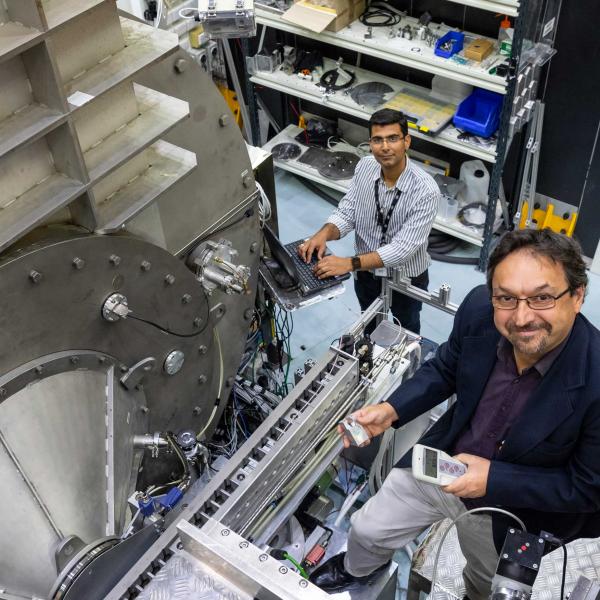

Dr Chris Garvey of ANSTO led research using X-ray techniques at the Laboratoire de Physique des Solides in Paris

Not all the news about plastic in the ocean is what we expect. In fact, it may be not quite as bad as initially thought. This comes as welcome information as we are celebrating National Science Week with an oceans theme.

Recent research published in Environmental Science and Technology led by an ANSTO scientist has found that the structural degradation of plastic in the ocean facilitates its entry into the natural carbon cycle efficiently as carbon dioxide.

The research was an investigation of the fragmentation of packaging into microplastics in the ocean. The work does not diminish the serious threat to wildlife from large pieces of packaging but draws important conclusions to the factors determining the lifetime of plastics in the environment.

The study was led by Dr Chris Garvey (Instrument Scientist at ANSTO’s Australian Centre for Neutron Scattering). Chris is currently a Fellow of the Lund Institute of Advanced Neutron and X-ray Science while based at the University of Malmö in Sweden. The work brings important understanding of the molecular scale physical mechanisms which enable the fragmentation of plastics into the ocean.

“Cellulose waste, including cardboard and paper, enters the carbon cycle by a well understood process. In recent years plastics, and in particular polyethylene, which originate from fossil fuels, have replaced paper as a barrier material for packaging. It is important to understand how this carbon, from a fossil pool, enters the carbon cycle” said Garvey.

Obviously with exposure to UV sunlight and oxygen in the ocean plastic begins to get brittle, crack and break into smaller pieces. Garvey and his associates wanted to know the molecular scale process leading to embrittlement and if these processes slow or hasten the chemical degradation of plastics.

The microplastics used in the experiments included samples that were collected in the tropical waters of the Caribbean as part of the Atlantic gyre. These samples were compared slightly larger weathered pieces of plastic from the same source and new samples that were the matching source of the weathered pieces.

The microplastics, which were about a millimetre in size, had been in the water a long time but there is no way of knowing when they entered the ocean other than they represent significant fragmentation of the original packaging.

However, probes with analytical techniques, most specially small and wide angle X-ray and Raman scattering identified important changes to the microstructure.

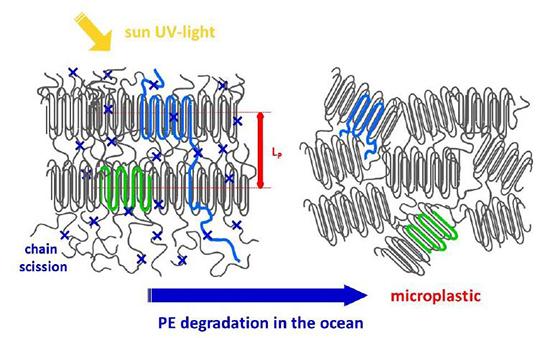

Plastics, in this example, polyethylene, consist of extremely long molecules which span many layers of alternating layers of crystalline polymer chains forming a lamella structure.

This is the normal structure of polyethylene produced by injection moulding which is used for packaging. The natural tendency of the long chain molecules is to crystallise and this process is frustrated by the entanglement of the polymer chains between the crystalline lamellae.

Lamella structures degrading Credit: Marianne Imperor, University Paris-Saclay

UV radiation in sunlight causes the chains to be cut. This has implications for the major degradation pathway, which ultimately converts the polymer chains into carbon dioxide.

“This releases the kinetic arrest, so the polymer starts to crystallise slowly again and this crystallisation process disrupts the lamella structure,” explained Garvey.

“When the lamella is disrupted, it is no longer such an effective barrier and oxygen can diffuse more easily into it,” he said.

In the study of polyethylene from different packaging, wide-angle X-ray scattering provided an indication of the nanoscale fragmentation of the crystalline layers and an increase in the fraction of crystalline polymer.

Small-angle X-ray scattering demonstrated loss of the alternating layers of amorphous and crystalline polymer.

Low frequency Raman scattering revealed little change in the thickness of the lamella during degradation.

The continuous barrier of the crystalline lamellae, and its barrier to oxygen diffusion into the plastic, is replaced with fragmented nano-domains which should afford a less effective barrier to oxygen permeation into the plastic. This change further catalyses the further degradation of the material by oxidation.

Garvey usually undertakes X-ray scattering at ANSTO. However, these X-ray scattering studies were part of a visiting professorship supported by the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) at the University Paris-Saclay in a laboratory, which can be regarded as the birthplace of small angle X-ray scattering.

The research is a continuation of previous work on environmental degradation of polymers with applications to agriculture, chemical transport and domestic packaging.

This paper has been published in in Environmental Science and Technology.

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c02095