Published on the 15th February 2022 by ANSTO Staff

Key Points

-

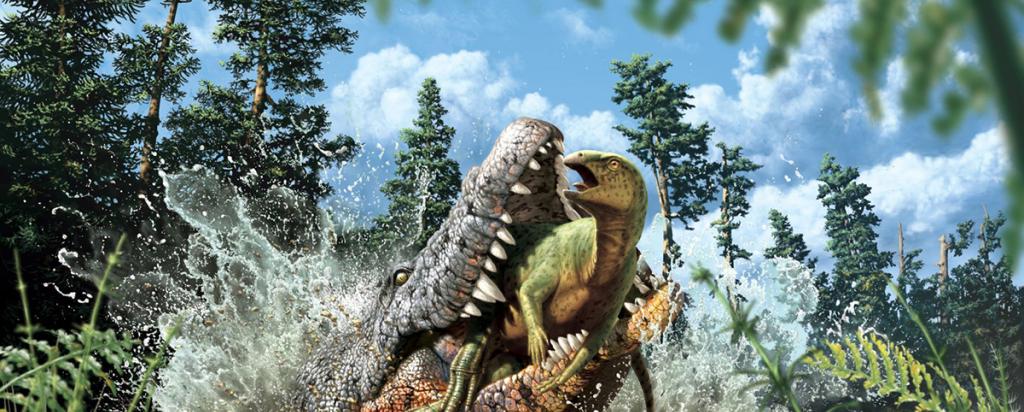

Advanced nuclear and synchrotron imaging has confirmed that a 93-million-year-old crocodile found in Central Queensland devoured a juvenile dinosaur based on remains found in the fossilised stomach contents

-

The discovery of fossils was made by a team from the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum and the University of New England who carried out the investigation with ANSTO scientists

-

Neutron and synchrotron instruments penetrated rock to reveal and reconstruct the concealed fossilised contents

Advanced nuclear and synchrotron imaging has confirmed that a 93-million-year-old crocodile found in Central Queensland devoured a juvenile dinosaur based on remains found in the fossilised stomach contents.

The discovery of the fossils in 2010 was made by the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum (QLD) in association with the University of New England, who are publishing their research in the journal Gondwana Research.

The research was carried out by a large team led by Dr Matt White of the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum and the University of New England.

The crocodile Confractosuchus sauroktonos, which translates as ‘the broken crocodile dinosaur killer’ was about 2 to 2.5 metres in length. ‘Broken’ refers to the fact that the crocodile was found in a massive, shattered boulder.

Early neutron imaging scans of one rock fragment from the boulder detected bones of the small chicken-sized juvenile dinosaur in the gut, an ornithopod that has not yet been formally identified by species.

Dr Joseph Bevitt and Dr Matt White with the sample on the Imaging and Medical beamline at ANSTO's Australian Synchrotron

Senior Instrument Scientist Dr Joseph Bevitt explained that the dinosaur bones were entirely embedded within the dense ironstone rock and were serendipitously discovered when the sample was exposed to the penetrative power of neutrons at ANSTO.

Dingo, Australia’s only neutron imaging instrument, can be used to produce two and three-dimensional images of a solid object and reveal concealed features within it.

“In the initial scan in 2015, I spotted a buried bone in there that looked like a chicken bone with a hook on it and thought straight away that it was a dinosaur,” explained Dr Bevitt.

“Human eyes had never seen it previously, as it was, and still is, totally encased in rock.”

The finding led to further, high-resolution scans using Dingo and the synchrotron X-ray Imaging and Medical Beamline over a number of years.

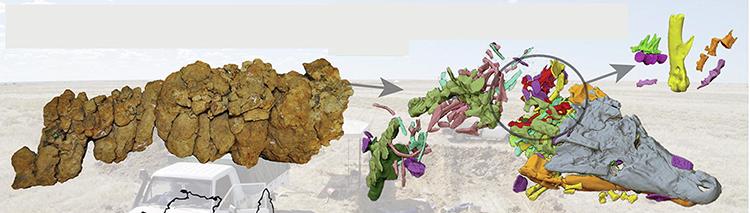

The unprepared rock samples containing the fossilised crocodile. Right: 3D images of the encased crocodile reconstructed with the Imaging and Medical Beamline, and inset, the stomach contents revealed using the Dingo neutron imaging instrument.

“3D digital scans from the Imaging and Medical Beamline guided the physical preparation of the crocodile, which was impossible without knowing precisely where the bones were,” said Dr Bevitt.

Conversely, the fragile samples had to be carefully reduced to a size that synchrotron X-rays could penetrate for high-quality scanning.

“The results were outstanding in providing an entire picture of the crocodile and its last meal, a partially digested juvenile dinosaur.”

It is believed to be the first time a synchrotron beamline has been used in this way.

IMBL Instrument scientist Dr Anton Maksiimenko assisted the investigative team to push up against the power limits and finetune the facility to successfully scan the large samples.

Dr Bevitt explained that the team used the full intensity of the synchrotron X-ray beam to achieve the results on dense rock.

Together, Drs Bevitt and White did all the data processing and importantly, developed new software mechanisms for processing and merging all data sets of this fragmented crocodile. In this way, the crocodile was reconstructed as a digital, 3D jigsaw puzzle.

To confirm the dinosaur was actually in the gut of the crocodile, the team observed infilled worm tunnels, plant roots and geological features that extended between rock fragments.

“The chemistry of rock provided the evidence, said Dr Bevitt.

Investigators think it is likely that the crocodile was caught up in a megaflood event, was buried and died suddenly.

“The fossilised remains were found in a large boulder. Concretions often form when organic matter, or say a crocodile, sinks to the bottom of a river. Because the environment is rich in minerals, within days the mud around the organism can solidify and harden because the presence of bacteria,” explained Dr Bevitt.

The specimens are now on display at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum, Winton.

The finding has been reported widely in the media.