Published on the 16th September 2022 by ANSTO Staff

Researchers have discovered a 380-million-year-old heart – the oldest ever found – alongside a separate fossilised stomach, intestine and liver in an ancient jawed fish, shedding new light on the evolution of our own bodies.

The new research, published today in Science, found that the position of the organs in the body of arthrodires – an extinct class of armoured fishes that flourished through the Devonian period from 419.2 million years ago to 358.9 million years ago – is similar to modern shark anatomy, offering vital new evolutionary clues..

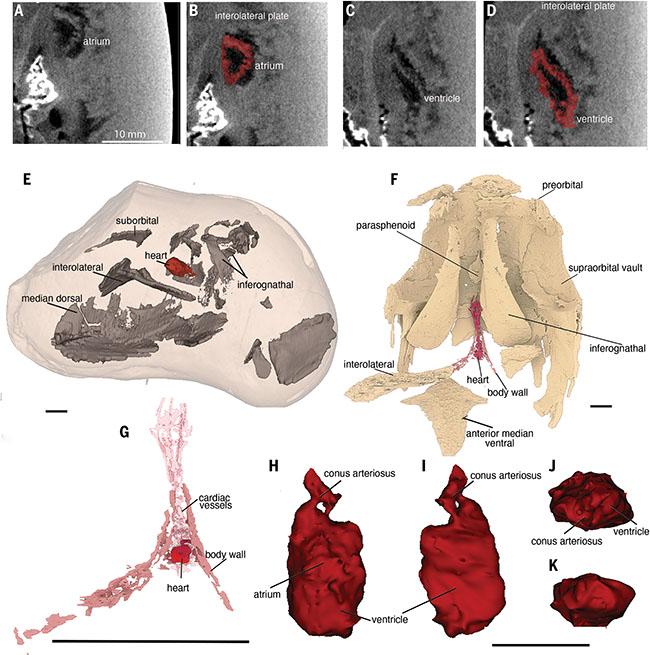

Enlisting the help of scientists at ANSTO in Sydney and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France, researchers used neutron beams at ANSTO and synchrotron X-rays to scan the specimens still embedded in the limestone concretions. They were able to construct three-dimensional images of the soft tissues inside them based on the different densities of minerals deposited by the bacteria and the surrounding rock matrix.

“The Gogo fish represents one of the best-preserved fossil sites of the Late Devonian (approximately 375 million years ago) in the world, having 3D preservation of original bones and mineralised muscle and organs,” said Dr Joseph Bevitt, a co-author on the paper published in Science today.

“However, the preferred method of removing the fossil from the surrounding rock, acetic acid digestion, destroys the soft tissue and organs."

When the lead researcher John Curtin Distinguished Professor Kate Trinajstic, from Curtin’s School of Molecular and Life Sciences and the Western Australian Museum, split open a fist-sized rock nodule, she discovered that it contained an exceptionally well-fossilised fossil fish.

“As neutrons have a unique ability to penetrate through rock and have a unique sensitivity to the presence of organic remains, the research team used ANSTO’s high-resolution neutronCT instrument DINGO to non-destructively visualise the embedded soft-tissue remains, revealing the world’s oldest 3D heart," explained Dr Bevitt.

“In this case, the heart tissue stood out in bright white amongst the rest of the remains. The neutron data revealed that the heart was complex and S-shaped, made of two chambers with the smaller chamber sitting on top.

“The heart of this ancient fish was located under its gills, like sharks today.

“Neutron imaging at ANSTO is increasingly being used by the palaeontology community to reveal internal body structures that are not visible with traditional X-ray tomography,” said Dr Bevitt.

Prof Trinajstic said the discovery was remarkable given that soft tissues of ancient species were rarely preserved, and it was even rarer to find 3D preservation.

Collaborating organisations also included Flinders University, Museums Victoria, Uppsala University (US), European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (France), Monash University, and the South Australian Museum.

The Gogo Formation, in the Kimberley region of Western Australia where the fossils were collected, was originally a large reef.