Published on the 15th November 2023 by ANSTO Staff

Key Points

-

NZ researchers have reported a minimum of 3.5 million years for fossilised footprints of the ancient flightless bird, the moa

-

This is the first known instance of moa footprints found in Te Waipounamu/South Island and represents the second earliest fossil record of moa in NZ

-

Cosmogenic nuclide dating of sand and gravel in which the footprints were found, determined the ages at ANSTO's Centre for Accelerator Science

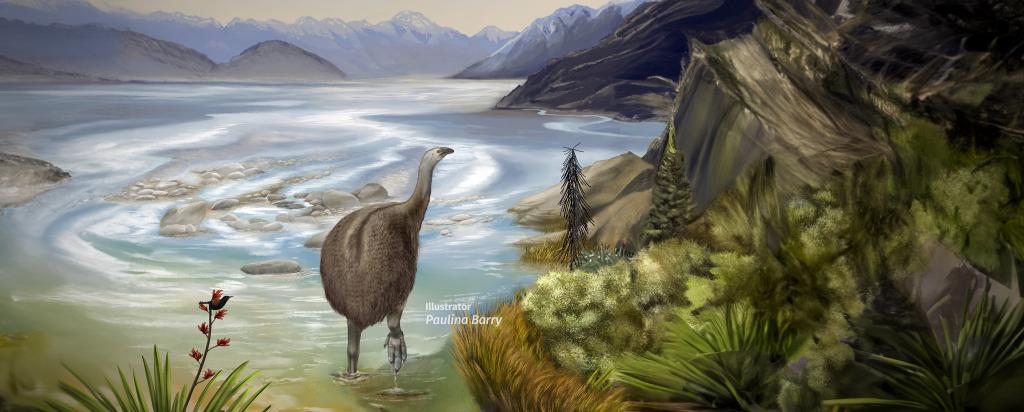

Banner image by Paulina Barry

Cosmogenic nuclide dating, a method commonly used in dating coastal areas and alluvial riverbeds for landscape reconstruction, is also useful to calculate the age of trace fossils, such as a footprint, where no remains of the animal are preserved.

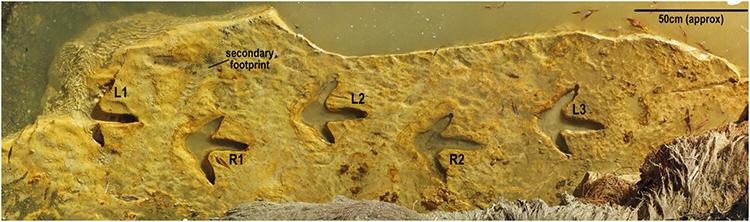

ANSTO scientist, Dr Klaus Wilcken of the Centre for Accelerator Science, used this method to determine the ages of layered sand and gravel samples, in which seven footprints of the flightless bird, the moa, were found on the South Island in New Zealand in 2019.

In research published today in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, researchers from the Tūhura Otago Museum, University of Otago, Victoria University of Wellington and Aukaha reported a minimum burial age of 3.5 million years.

“We calculated that age with a range of +1.62/-1.18 million years, suggesting the Late Pliocene period and, potentially extending to the Early Pleistocene, “ said Dr Wilcken.

“This method involves measuring the isotopes, 26Al and 10Be produced by cosmic radiation interacting with rocks near the surface.“

“It is certainly one of the more unusual rock samples we have dated, “ he added.

“The ANSTO contribution was significant. Without it, we would not have been able to put the footprints into evolutionary context. With it, we were able to identify these footprints as being from the Emeidae family and most likely the Pachyornis genera (similar to that of the heavy-footed moa as well as the other faint footprint that was made in the clay layers above the track from a Dinornithidae family and most likely the Dinornis genera.

“By 3.6 million years ago a least one species of moa had reached a gigantic size similar to the South Island Giant moa,” said lead author Kane Fleury, Curator, Tūhura Otago Museum.

Sand and gravel were collected by the New Zealand research team from a 30-meter-high cliff, with two samples from different depths and one from downstream.

The samples were processed in a laboratory at the Centre for Accelerator Science to extract the beryllium and aluminium isotopes.

To find the burial age, a model was developed, considering factors like burial depth and time. The model was tested against measured concentrations of the 26Al and 10Be isotopes on the Sirius accelerator.

This is the first known instance of moa footprints found in Te Waipounamu/South Island and represents the second earliest fossil record of moa.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2023.2264789

Media information from Tūhura Otago Museum

Research published today in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand has provided some long-awaited updates on the mysterious Maniototo moa footprints.

In 2019, Ranfurly man Michael Johnston was out walking his boss’s dogs when he spotted seven fossilised moa footprints in the bed of the Kyeburn River. They went down in history as the first moa prints to be found in the South Island. The ensuing extraction (a collaborative effort involving Otago Museum, the Department of Geology – University of Otago, Kāti Huirapa Rūnaka ki Puketeraki, and Te Rūnanga ō Ōtākou) attracted international media interest and raised several questions: how tall and heavy was this bird? What variety of moa was it, and how long ago was it walking through the area?

Those queries have just been answered in a paper titled ‘The moa footprints from the Pliocene – Early Pleistocene of Kyeburn, Otago, New Zealand’. For its lead author, Kane Fleury (natural science curator at Tūhura Otago Museum), the release of this research marks a satisfying milestone in a process that began when he responded to Michael Johnston’s Facebook Messenger inquiry four years ago.

“This whole experience has been incredible”, he says. “A lot of luck goes into the fossilisation of footprints—conditions had to be absolutely perfect for these tracks to be preserved, and they had to be just right again to expose the fossils without destroying them. The public really got on board with how spectacular this find was and had heaps of questions, so it’s a great feeling to be able to follow up with some answers.”

A team consisting of researchers from Tūhura Otago Museum, the Department of Geology – University of Otago, Victoria University of Wellington, the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, and Aukaha has established that the seven footprint impressions were left by a member of the Emeidae family, most likely of the Pachyornis genus. This would likely make it a relative of the heavy-footed moa, a variety noted for being particularly bottom-heavy with unusually short and thick legs. (If you’d like to see one for yourself, there is a skeleton on display in the Museum’s Southern Land, Southern People gallery.)

To the researchers’ surprise, a 3D photogrammetry model of the fossil site later revealed the presence of a second moa, this time from another family: Dinornithidae. Just one extremely faint print had been preserved in the riverbed, and its dimensions suggest the bird may have been a member of the Dinornis genus, which includes the largest-known species of moa—the South Island giant. Although not approaching those behemoths in weight (fully grown females are thought to have been up to 250 kg), the Kyeburn precursor was still impressive at an estimated 158 kg.

The trackway left by the Emeidae moa gave researchers more to work with, so in addition to modelling its height and weight (1095 mm at the hip and 85 kg), they were able to estimate that it was walking at a slow 2.6 km/h. The most significant finding, however, is that it was doing so at least 3.6 million years ago. This was ascertained through cosmogenic nuclide dating, a cutting-edge technique used to calculate when sediments in the Kyeburn’s bank were buried. Their age tells us two key things: the footprints are the second-earliest fossil record of moa and, given the dimensions of the lone Dinornithidae print, moa had attained their legendary gigantic size by the Pliocene.

As Kane explains, many moa remains or traces are extremely recent in geological terms—less than 10,000 years old. However, the Kyeburn prints were buried 3.6 million years ago, so they offer a rare glimpse into a period of moa evolution that is not well understood, making them still more significant. “We’ve cracked that door open a bit more”, he adds.

Unusually for a major paleontological find, this discovery was shared with the public before it had been studied, and Kane thinks the high level of community interest helped drive the research process. “The Museum had to set up an FAQ page”, he notes. “The project really captured people’s imaginations, and it was fantastic to have the community see this side of what we do as an institution. Research is a big part of our mission.”

Tūhura’s director, Ian Griffin, agrees, adding that the Museum plays a vital role as a conduit between its community and researchers. “I’m so proud of the team here. Despite our institution receiving no government funding for this important mahi, as soon as we heard about what we realised was an internationally important discovery, we linked up with experts from NZ and elsewhere and assembled a team that carried out one of the coolest and most important fossil recoveries in recent times. I’m stoked to see what’s come of that!”

For more information, please contact Charlie Buchan, Tūhura Otago Museum Marketing Manager

Charlie.Buchan@otagomuseum.nz

|03| 474 7474 ext. 845