Published on the 19th July 2023 by ANSTO Staff

Key Points

-

Food science researchers have developed a promising method to make spray dried beta carotene microcapsules more stable

-

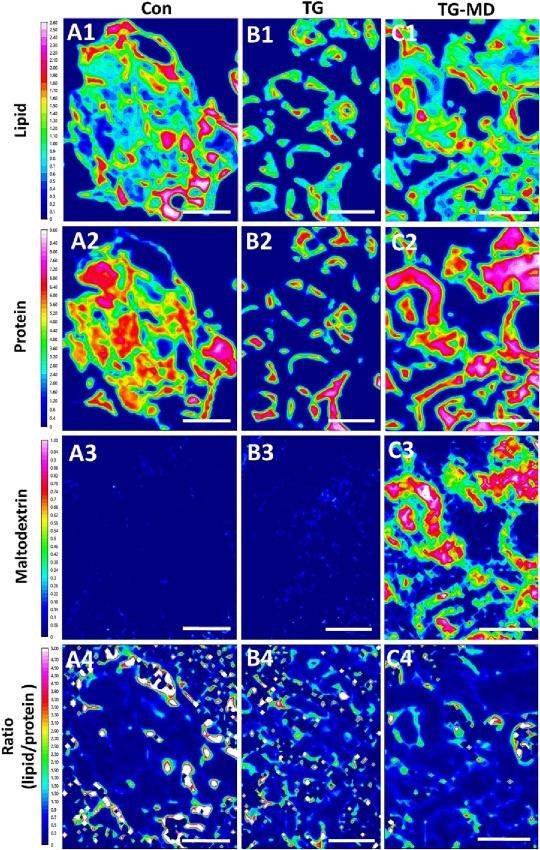

Cross-linking dairy and plant proteins with an enzyme and adding maltodextrin improved the encapsulation efficiency and reduced the porosity of the microcapsules, essentially making the particle wall more stable.

-

Scientists from UNSW used the Infrared microspectroscopy beamline to observe what was going on at the surface of microparticles

Food science researchers from the University of NSW have developed a promising method to make spray dried beta carotene (β-carotene) microcapsules more stable as reported in a paper published in Food Chemistry.

Beta carotene microcapsules are used as a dietary supplement to provide a source of beta carotene, which is converted by the body into vitamin A, an essential nutrient required for normal growth, vision, immune function, and overall health.

The lead author, Dr Woojeong Kim, who was a PhD candidate at the time supervised by Prof Cordelia Selomulya at UNSW, proposed a novel blend of plant and dairy proteins with and without the carbohydrate maltodextrin as carriers to encapsulate β-carotene.

They found that cross-linking the proteins with an enzyme and adding maltodextrin improved the encapsulation efficiency and reduced the porosity of the microcapsules, essentially making the particle wall more stable.

The β-carotene was successfully preserved for at least 8 weeks, with an encapsulation efficiency of over 90%.

Microencapsulation is a technique used to protect sensitive substances by encapsulating them in a specific material. The choice of materials is important for the effectiveness and stability of the encapsulation.

Spray drying is a popular method for encapsulation in the food and pharmaceutical industries, as it transforms liquid materials into powder form. However, controlling the amount of surface fat in spray dried particles is challenging.

The researchers used an advanced technique on the Australian Synchrotron’s Infrared Microspectroscopy (IRM) beamline, to analyse the surface composition of the microcapsules and found that the cross-linked protein-maltodextrin complex helped to reduce the amount of oil exposed on the surface.

Synchrotron-FTIR microspectroscopy is used to obtain high-quality spectra at a small scale, allowing for the examination of microparticles.

“The IRM technique allowed us to look at the molecular level at what was going on at the surface with the cross linking of the protein structures, particularly how much of the surface is protein,” explained Dr Kim, whose investigation of dairy and plant proteins as food emulsifiers was published in a paper in Trends in Food Science and Technology in 2020.

“It gave us in depth characterisation information about what happens when you cross link the dairy and plant protein and not just mix them together,” she added.

“It also provided some useful secondary structural information about the proteins.”

Other members of the research team included Qianyu Ye and Yong Wang of UNSW,

“Since the first development of the “macro-ATR” technique in 2016, our beamline has proved to be very useful in various food and drug delivery applications to investigate chemical distributions at the surface and interfaces critical for this research. Other highlight includes mapping the protein and lipid distributions of a fresh commercial mozzarella cheese right at its storage temperature (4 oC) without any sample pretreatment to ensure the accuracy of the results.,” said beamline scientist Dr Pimm Vongsvivut, a co-author on the paper.

Prof Selomulya said the cross-linked pea and whey protein-maltodextrin complex was a promising ingredient more broadly for functional foods.

Prof Selomulya is the Research & Commercialisation Director at Future Food Systems, a cooperative research centre.

The optimisation of food and fibre production and processing, enhanced food safety and the minimisation of wastes in food production is an Australian research priority.