Published on the 22nd March 2016 by ANSTO Staff

ANSTO and the University of NSW, Australia (UNSW) have launched an initiative with a citizen scientist component that will enable tracking of the movements of waterbirds between regional wetland sites across Australia.

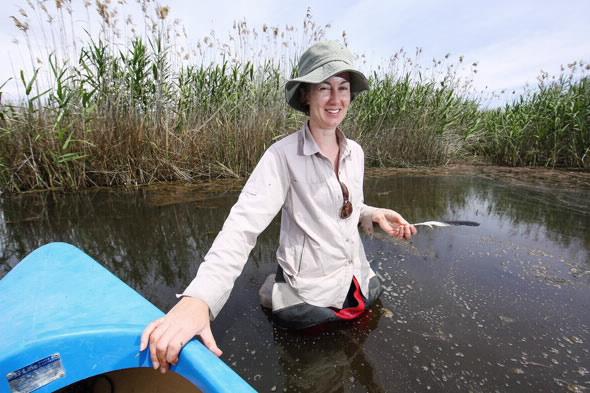

“There are some big questions about water bird movements,” said project leader Dr Kate Brandis (pictured above), an environmental researcher at ANSTO and UNSW who is an expert on colonially breeding water birds.

“Colonial birds come together in their thousands on flooded inland water systems to breed. Then they disappear into much smaller groups. And then you might not see them for years. We would like to determine where they go and where they come from when they come back,” explained Brandis.

The project will involve the creation of a unique Feather Map that will help identify patterns of waterbird movement that can be built up from individual feathers. “It will help us identify which wetlands are really important for certain species.”

“We are primarily interested in inland wetlands where you find birds such as the colonial straw-necked and glossy ibis, as opposed to coastal estuarine wetlands” said Brandis.

Wetlands around Australia are under threat from reduced river flows and flooding, drought, climate change and land use changes. Wetlands are habitats that are critical for Australia’s water birds. They provide places for nesting, feeding and roosting. For many species of water birds, flooded wetlands are essential for nesting. Without floods and river flows, many water birds don’t breed.

Water resource regulation is impacting on wetlands. “We’ve got to a stage where we have environmental flow allocations and managers are making decisions about when water can flow to wetlands.”

Enlisting citizen scientists to collect feathers on the ground or feathers from deceased birds from inland wetlands is an inexpensive and non-invasive method to acquire samples. “It also avoids welfare issues with tagging and tracking individual birds.”

Traditional approaches, using GPS or satellites are very costly and provide only small samples. In North America, they use precipitation gradients to identify where the birds came from but rainfall in Australia is too variable for that approach.

Brandis collected feathers during an earlier pilot; a dietary study conducted in collaboration with ANSTO environmental researcher Debashish Mazumder, at Lowidgee on the Lower Murrumbidgee and received feathers from colleagues at other wetlands.

By analysing isotopes of carbon and nitrogen, they were able to discern a significant difference in the feathers and link them to wetland sites. “Identifying the elements with another nuclear technique can also help you distinguish between wetland sites,” said Brandis.

Brandis applied for a fellowship to use isotope analysis to identify water bird movement across Australia that has been funded by ANSTO until 2018. UNSW is jointly supporting the research.

“I have collected feathers in Western Australia and have colleagues all along the Murray Darling Basin collecting feathers for me.”

The initiative is at the stage where the research team, which includes Debashish Mazumder and Suzanne Hollins from ANSTO and Richard Kingsford from UNSW is determining the order of methodologies for analysing of the feathers.

Brandis has a PhD student who is washing the collected feathers to collect zooplankton eggs as there are specific wetland birds, such as the pink eared ducks and freckled ducks that eat them.

Zooplankton species are important as the basis of the food web. “They get transported from wetland to wetland on the feathers of birds,” said Brandis.

High resolution X-ray fluorescence (ITRAX-XRF) provides information about the mineral elements in the feathers. The measurements will be managed by ANSTO's ITRAX Facility Officer Patricia Gadd (pictured above).

“The isotope analysis of carbon and nitrogen gives us an idea of the diet, whether it is a plant eating or fish eating bird, which helps narrow down the species, such as a cormorant or a swan,” said Brandis.

The isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen provide information about the water.

Another question they hope to answer by sampling during breeding events relates to whether birds use only the breeding site where they were born. This is known as natal site fidelity and there is some debate as to whether it exists at all.

“We do not know if they only go back to the wetland site, where they hatched.“

The information gained by the initiative is important for understanding the ecology and life cycles of water birds and water bird populations and ensuring that populations of Australia’s water birds are maintained or increased.

The Citizen Science contribution to the Feather Map encourages people to collect feathers and post them to the research team.